Commodities Study Note: Fuel Oil and Bunker Marekt

Motivation:

This post is more of a walk-through of my own study notes created to help me prepare for a job interview and learn more about the commodities industry. Previously my exposure to commodities is mainly about crude oil markets of WTI/Brent. Thus I consider this primer is serving the purpose of demystifying.

What’s unique about commodity as an asset class is about twofold: (1) Physical Delivery and (2) Grades.

Physical Delivery:

What differs commodities is that they are largely driven by commercial usage, e.g., vessel voyage needs fuel, infrastructure development needs iron ore, and a variety of food products need soybeans. This expectation for present or future consumption naturally leads to requirements for effective logistics management such as storage, warehousing, scheduling, and minimizing any potential disturbance or shock to the supply chain.

Grades:

Compared to Delta-1 or FX, almost any commodity product has an additional layer of complexity, which is the Grades.

So far we’ve discussed a lot of trading examples using FX. In FX, one dollar is just one dollar - it would be hilarious to even think that there’s a “premium” dollar and a “standard” dollar. But in commodities, grades are really critical in case of agricultural products of rice, wheat, soybean, etc. Contracts involve energy, precious and industrial metals also specify the grade traded. Grades are usually assigned based on the purity or quality of the products. The exact definition varies from contract to contract and also from exchange to exchange.

It’s similar to the different ratings and tranches in Credit trading, but in a much more granular way. An equity trader may consider the alternatives in a particular thematic ETF, e.g., for exposure to Japanese stocks, one may choose BBJP, EWJ, or DXJ, each has its own unique attributes such as fees.

A side note is that “preferred habitat” theory in Rates also works in commodities: we know that in government bonds, say UST, a certain type of investors may crowd a certain maturity of the Yield Curve, e.g., 10y-30y for pension funds to beat the inflation while 5y-10y for asset managers.This observation also applies to commodities, e.g., a boutique coffee shop is only sourcing certain premium coffee beans.

Bunker Market:

First, a quick word of caution. I would say after my research I find that bunker is a very niche market. I won’t recommend diving further into the product details unless one is going for a full time job in bunker sales-trading or maritime industry.

That being said, if a global markets practitioner is indeed preparing for a job and getting serious about the products, he or she will be assured of finding some familiarity and linkage to the broad markets business, as bunker has a strong link to the crude so macro traders or salespeople won’t find the products detached from the macro market too much. And for those who are well-versed in derivatives, the mechanism for bunker is still the same just different underlyings.

Now we go back to the bunkers. The word “bunker” originally refers to a container in which the fuel for the ship is stored. Therefore by extension,

- “Bunkering” means fueling a ship

- “Bunkers” refers to fuel used by ships

- In the broadest sense, “Bunker Fuel” refers to any fuel that is used on a ship

Bunker Fuel is part of a broader family known as Fuel Oils

- Fuel Oils have two categories: Distillates (25% market share) o Residuals (75% market share). Residual Fuel dominates with ¾ market share.

Fuel Grades Classification:

First based on the chemical components there are two broad categories:

- Marine gas oil/marine diesel oil (MGO/MDO)

- Intermediate Fuel Oil (IFO): IFO380, IFO500, Low Sulfur (LS) 380, IFO180, LS180, and IFO700

More specifically, there are 3 major grades that are closely watched by bunker practitioners:

- VLSFO: Very Low Sulfur Fuel Oil

A type of HFO (Heavy Fuel Oil) blended to meet the 0.5% sulfur cap imposed by the IMO 2020 regulations

Use: widely adopted by shipping companies to comply with the new sulfur regulations. It has the environmental emphasis: reduced sulfur emissions, more compliant with international environmental standards

- MGO: Marine Gas Oil

A lighter, distillate fuel oil with lower sulfur content compared to HFO

Used by smaller vessels or auxiliary engines on larger ships; it’s preferred in Emission Control Areas (ECAs) due to stricter sulfur limits. - Environmental: lower sulfur content than HFO

- IFO380: Intermediate Fuel Oil

- IFO380 and IFO180 are the most widely used Fuel Grades among the fuel grade categories, due to (1) lower cost compared to other Fuel Grades, (2) compatibility that most ship engines can combust the IFO380.

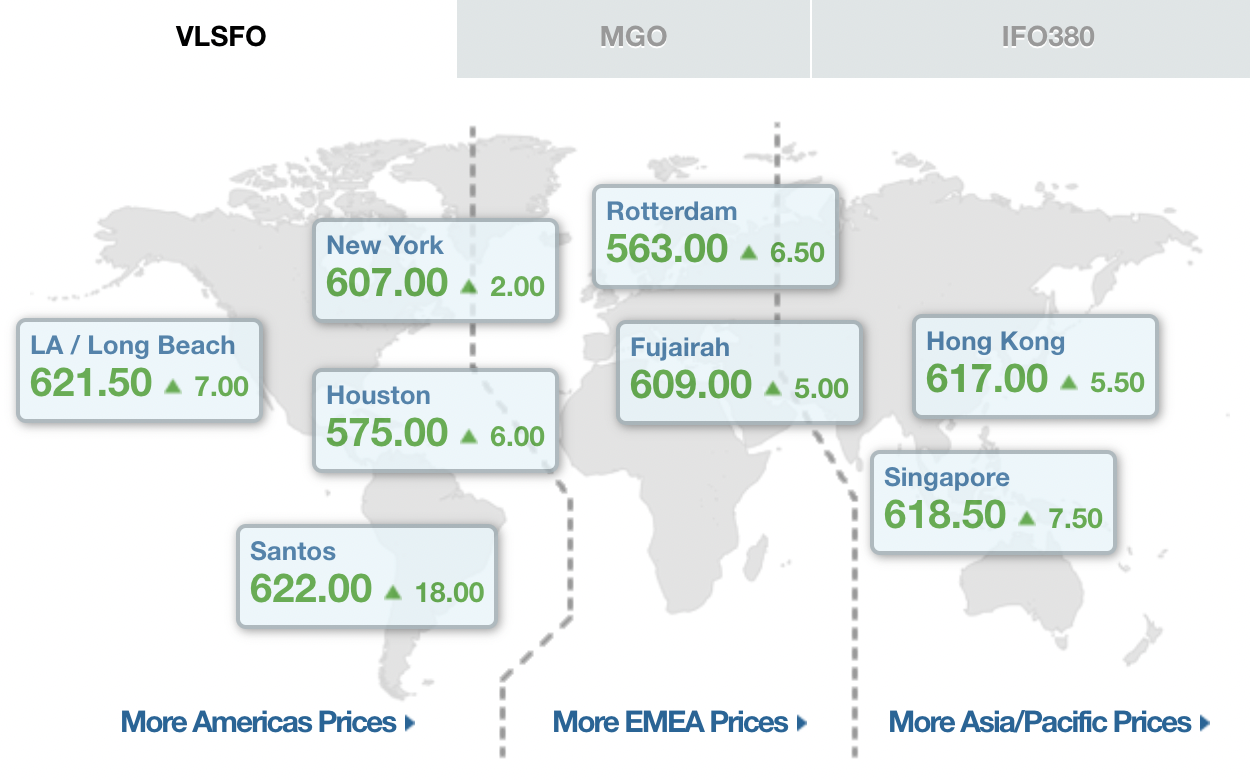

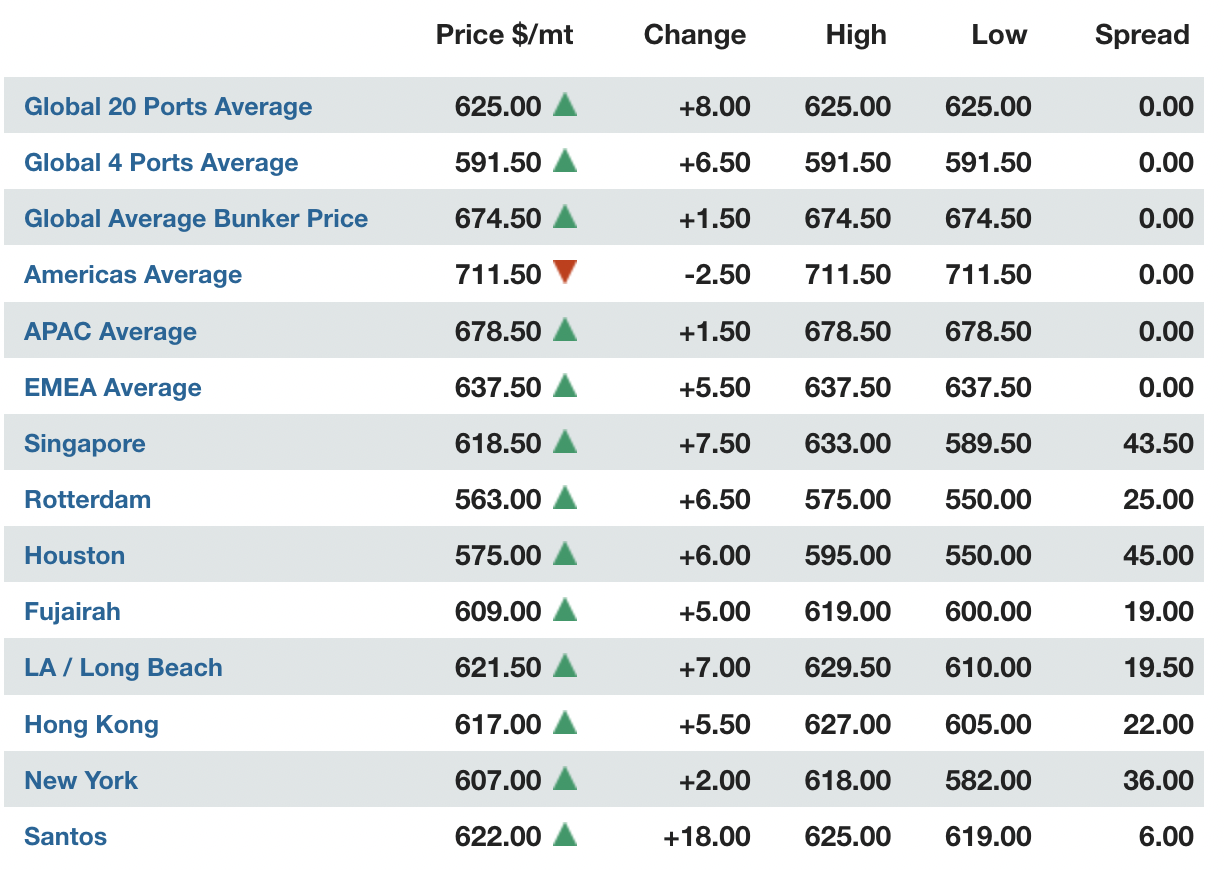

Where to find some price data?

The website, Ship & Bunker, is the most read marine fuel-focused publication. It gives daily and historical bunker prices of the major bunker markets.

Here we give an example of the global prices of the three bunker grades (VLSFO, MGO, IFO380), taken from the above website:

No need to be panic here about the chemical components! Traders and brokers don’t need to be a chemistry graduate to trade the product. But it’s useful to understand the different grades since the clients have different vessels and may have different preferences. Also knowing the technical chemical definitions can help traders anticipate how a potential future regulation, e.g., sulfur restriction, may shift the market’s preference. That’s why you may find a lot of practitioners come from mining or geology majors. :)

Major Regional Centers and Ports:

Globally, there are 3 regional centers for bunker by shipping activities: Singapore, Rotterdam, Houston. With Singapore being the largest, not Houston

Thus, the implication is that even though bunker price in Rotterdam is cheaper than Singapore, it doesn’t help much if the ship is not stopping at that particular port.

- How about arbitrage opportunities between different global ports? In theory, yes, but in reality it’s very unlikely to be profitable due to logistics and operational constraints.

Market and Desk Structure:

This is just my own research, not based on actual desk experience.

It’s an OTC-based market: traders talk to the shipowners, operators, or charters to negotiate and customize the deal and the logistics for the bunker fuel needed. Traders/Brokers are more like sales-traders in a bank. They trade the Spot (or so-called Physical) market while hedging is done by another desk or an outsourced risk solution providers.

The product itself is highly volatile and the contract notional is huge. For a voyage from Houston to Rotterdam, over 50% of the voyage cost will be for the bunker fuel, which can be several millions in notional. We will talk more about the reason why bunker prices are so volatile in details later.

It requires Physical Delivery to the ship for voyage: this “settlement” is usually not covered by MO/BO team. And a bunker trader or broker needs to communicate with the port and make sure a smooth operation.

Regulated in a different way: we won’t talk about regulation details here but one interesting example I came across is that brokers are allowed to use private messaging platform like WhatsApp to conduct business, while for traders in a bank, using these private platform can result in huge compliance issues and larges fines for the banks. In other words, there are fewer restrictions on the traders/brokers but more on the products themselves. Like we mentioned that the sulfur content is a huge concern and once IMO2020 is out, ship operators and charters need to quick consider the alternative grades that might be cheaper but less efficient

Economics & Fundamentals:

This is the section that one future bunker trader needs to be carefully prepared when asked about market dynamics, i.e., “what moves the bunker price”. Here we will list some of the economic forces but they come from economics theory and can’t be replaced by more valuable desk experiences.

First question, suppose you are a ship operator, what are the factors from the revenue/expenses?

From the revenue side, the risk of operating a vessel is mainly the volatility of Freight Rates – which can be mitigated using Freight Derivatives (we won’t cover here since it’s actually another market)

For Operating Costs, they are covered by the shipowner under both the voyage charter and time-charter agreements – including manning, repairs and maintenance, stores and lubes, insurance, broking commission, and admin

For Voyage Costs, they are covered by the shipowner under a voyage agreement and by the charterer under a time-charter agreement – Bunker Fuel, Port Fees, Tugs and Canal Dues. One good thing to remember is that besides Bunker, the rest of costs usually predictable, while Bunker Fuels are notoriously volatile and accounts for 50%-60% of the total voyage costs, the main variable to control from the cost side of operating a vessel.

- E.g., a fully operational ULCC vessel consumes about 8,000 tons of bunker for one voyage from Arabian Gulf to Europe and about 180 tons Bunker daily, for a 40-day trip under normal weather. If the bunker prices in Rotterdam were at $382.8/mt, the total fuel cost will be about 3 million.

Second, what are the prices dynamics of bunker? Why they are so volatile?

Bunker Prices generally tend to move in line (have a high correlation) with Crude Oil Prices. E.g., a decision from OPEC meeting cutting supply will indirectly impact the bunker market

Demand of Bunker: of course due to the shipping needs from shipowners and vessel operators who have a vessel on a time-charter agreement

Supply of Bunker: major oil companies and independent companies as well as refineries

- Due to the highly volatile nature, bunker suppliers are reluctant to close deals more than one week ahead. This is where the brokers come in. They need to “work” the deal to get the best price possible

The alternative fuel market also impacts the bunker price:

- Prices for oil products are determined by Supply/Demand for each specific oil product, and also the price and availability of alternative fuel, e.g., Fuel oil is affected by the demand for power and the ability to generate it, but also the price of alternative energy like natural gas

Third, what about the Economic Forces in general?

Oil markets: Crude Oil market impacting the bunker market, e.g., OPEC’s decision to cutting supply, geopolitical risk, reserves of “Shale Oil”

Bunker stock levels: suppliers may intentionally withhold stocks in anticipation of higher prices; such dramatic increases tend to come up with an equally dramatic slump

Refinery practices: it’s difficult for bunker suppliers in many ports to guarantee a regular supply of bunker fuel throughout its different grades, since marine fuels represent less than 5% of the value of the petroleum products traded worldwide

Change in overseas competition: E.g., a fall in Singapore can influence Rotterdam and vice-versa. Both Rotterdam and Singapore prices can affect the Saudi Arabian ports prices

Delivery Methods: (1) taking directly from storage tanks, but it’s expensive if the ship comes in only for fuels; (2) typically bunkering is made by “barge” at the vessel’s berth or at anchorage. The competitiveness of the barge market since the extra costs linked to barge delivery vary widely and depend on the operators.

Random shocks: weather, port delays, field shutdowns, political events, army coups, OPEC, Russia, decision from the American Petroleum Institute (API)

To summarize:

Supply: mainly from the supply of Crude - Crude Oil market, refining capacity, oversea and local competition, bunkering methods

Demand: resulting from the demand for shipping, which means world’s economy, international seaborne trade, seasonality, political disturbance, transport cost

Supply/Demand, but only regional: Vessels only take bunker at a limited number of ports around the globe (as mentioned, Singapore, Rotterdam, Houston, sometimes Fujairah), the bunker price reflects certain situation of the supply/demand at a particular port or a particular region – which leads to differences in bunker prices of up to 50%

Factors that impact Bunker Price: - World’s economy, international seaborne trade, freight rates, fuel consumption, world tonnage, vessel speed

We mentioned that bunker prices are highly volatile. Then what are the factors or sources of volatility?

General macro economic conditions

Weather (e.g., Hurricane in Houston)

Political stability of oil-production countries (since bunker is the product of crude)

Bunker Trading and Scrubber Spread:

Like any trading in FICC, there’s always the spread consideration.

In the context of bunker fuel trading, the “Scrubber Spread” refers to the price difference between low-sulfur fuel oil (LSFO) and high-sulfur fuel oil (HSFO). “Scrubber” is used to reduce the sulfur.

This spread is significant because it reflects the cost implications and economic viability of using exhaust gas cleaning systems, commonly known as “scrubbers,” on ships.

HSFO is cheaper but brings more pollution, while VLSFO is more expensive but compliant with environmental regulations

Here is the historical Scrubber Spread, taken from the website Bunker Index:

A more detailed breakdown:

High-Sulfur Fuel Oil (HSFO): This is the traditional bunker fuel used by ships, which contains higher levels of sulfur (typically around 3.5%). The International Maritime Organization (IMO) regulations, particularly the IMO 2020 rule, mandate that ships must use fuels with sulfur content not exceeding 0.5% unless they are equipped with scrubbers.

Low-Sulfur Fuel Oil (LSFO): To comply with IMO regulations, ships must use LSFO, which has a sulfur content of 0.5% or lower, or install scrubbers that allow them to continue using HSFO.

Scrubber Spread: The spread is calculated by subtracting the price of HSFO from the price of LSFO. For example, if LSFO is priced at $600 per ton and HSFO is priced at $400 per ton, the scrubber spread is $200 per ton.

When the Spread is Wide: A larger scrubber spread indicates a higher cost differential between LSFO and HSFO. In such cases, investing in scrubbers becomes economically advantageous because the cost savings from continuing to use the cheaper HSFO can offset the investment and operating costs of the scrubbers over time.

When the Spread is Narrow: A smaller scrubber spread suggests a lower cost differential between LSFO and HSFO. In this scenario, the financial benefit of installing scrubbers is reduced, making it less attractive for shipowners.

The scrubber spread is a critical metric for shipowners and operators when making decisions about compliance strategies with sulfur emission regulations. It influences decisions on whether to invest in scrubbers or switch to low-sulfur fuels.

Hedging Risk:

Like almost any other asset class, bunker brokers also use instruments like Futures and Options

A little History of Hedging:

- The 1st Bunker Future was launched at Singapore Futures Exchange in 1988

- However, the early Bunker Futures failed with limited trading volume. Why?

- Recall that we mentioned bunker fuel is essentially driven by shipping activities and requires physical delivery to the ship.

Thus, it’s because of the nature of the bunker market where physical bunkers are taking place in different ports around the globe, while bunker Futures are for the delivery of bunker in specific locations, thus, these futures price don’t behave the same way as the physical bunker prices at global ports.

– In other words, in the early days this hedge choice is not effective at all. Nowadays there are more reliable bunker Futures traded at all the major shipping centers and are different from exchange to exchange.

Without an exchange-based Futures contract for hedging Bunker Price, people search for the alternative Cross-Hedging

It turned out a good cross-hedge for Bunker is the Energy in general (Crude Oil, Gas Oil, and Heating Oil)

Thus, Energy Futures are proven to be the best alternative for Bunker Futures in hedging against Bunker price

Cross-Hedge with Energy Futures

- Motivation is that there is a high correlation between Bunker and Crude Oil

- Recall Futures has a standardized unit called “lot”, each Lot in commodities is usually 1,000 tons.

Example:

- 06/15/2024: a shipowner fixes a contract to carry cargo from Houston to Rotterdam

- 07/15/2024: Voyage begins at Houston; 6,000 tons of IFO380 to be loaded

Right now (6/15), Brent traded at NYMEX, with 1 Lot = 1,000 barrels; a standard Brent Futures has 1 Lot; on 6/15, Brent Futures is $70/barrel, and IFO380 is $360.5/ton, for a total of 6,000 tons the total fuel cost is $2,163,000

But suddenly there is a high expectation that hurricane in Houston, damaging the refineries and causing bunker price to soar in the short run. The ship owner is concerned that on 07/15, price will go up, he will hedge Bunker Price increase by buying Brent Futures

How many Brent Futures to buy? - One standard Brent contract is 1 Lot = 1,000 Barrel, with $70/Barrel, one standard Brent future costs $70,000. This means matching total fuel cost, 31 (30.9) contracts

Now, on 07/15, Bunker Prices goes up to $364/ton and Brent crude Futures goes up to $74/barrel, what is PnL?

Futures we gain $4x31x1,000 = +$124,000 Physical we get: $-3.5x6,000 = -$21,000 We can say this is a portfolio of Spot and Futures

Perhaps the only thing that a derivative trader should take into consideration is that for fuels like bunker, the risk is the upside, not the downside like stocks, in other words, it’s the difference between Short-Hedge and Long-Hedge:

Short Hedge: protect against a loss from the price decrease of the asset, e.g., stocks, bonds

Long Hedge: protect against a loss from the price increase of the asset, e.g., Bunker Fuel

Note that there are five types of callouts, including: note, tip, warning, caution, and important.

This is an example of a callout with a caption.